Simple user model¶

This example works through a fit to a small one-dimensional dataset which includes errors. This means that, unlike the Simple Interpolation example, an analysis of the parameter errors can be made. The fit begins with the use of the basic Sherpa models, but this turns out to be sub-optimal - since the model parameters do not match the required parameters - so a user model is created, which recasts the Sherpa model parameters into the desired form. It also has the advantage of simplifying the model, which avoids the need for manual intervention required with the Sherpa version.

Introduction¶

For this example, a data set from the literature was chosen, looking at non-Astronomy papers to show that Sherpa can be used in a variety of fields. There is no attempt made here to interpret the results, and the model parameters, and their errors, derived here should not be assumed to have any meaning compared to the results of the paper.

The data used in this example is taken from

Zhao Y, Tang X, Zhao X, Wang Y (2017) Effect of various nitrogen

conditions on population growth, temporary cysts and cellular biochemical

compositions of Karenia mikimotoi. PLoS ONE 12(2): e0171996.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171996. The

Supporting information section of the paper includes a

spreadsheet containing the data for the figures, and this was

downloaded and stored as the file pone.0171996.s001.xlsx.

The aim is to fit a similar model to that described in Table 5, that is

where \(t\) and \(y\) are the abscissa (independent axis) and ordinate (dependent axis), respectively. The idea is to see if we can get a similar result rather than to make any inferences based on the data. For this example only the “NaNO3” dataset is going to be used.

Setting up¶

Both NumPy and Matplotlib are required:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Reading in the data¶

The openpyxl package (version 2.4.2) is used to read in the data from the Excel spreadsheet. This is not guaranteed to be the optimal means of reading in the data (and relies on hard-coded knowledge of the column numbers):

>>> from openpyxl import load_workbook

>>> wb = load_workbook('pone.0171996.s001.xlsx')

>>> fig4 = wb['Fig4data']

>>> t = []; y = []; dy = []

>>> for r in list(fig4.values)[2:]:

... t.append(r[0])

... y.append(r[3])

... dy.append(r[4])

...

With these arrays, a data object can be created:

>>> from sherpa.data import Data1D

>>> d = Data1D('NaNO_3', t, y, dy)

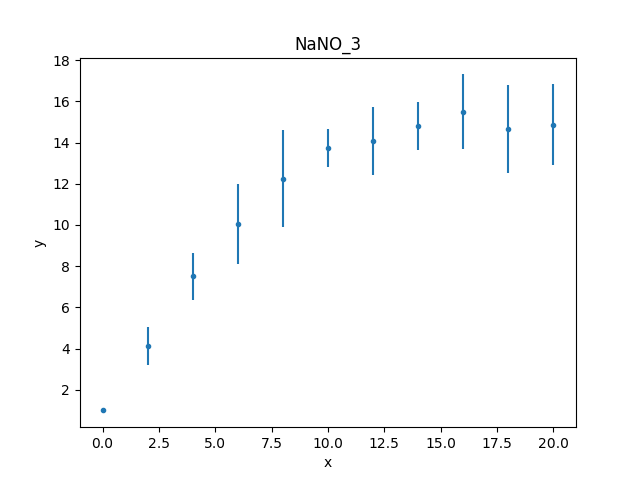

Unlike the first worked example,

this data set includes an error column, so the data plot

created by DataPlot contains

error bars (although not obvious for the first point,

which has an error of 0):

>>> dplot = DataPlot()

>>> dplot.prepare(d)

>>> dplot.plot()

The data can also be inspected directly (as there aren’t many data points):

>>> print(d)

name = NaNO_3

x = [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20]

y = [1, 4.125, 7.5, 10.0417, 12.25, 13.75, 14.0833, 14.7917, 15.5, 14.6667, 14.875]

staterror = [0, 0.9214, 1.1273, 1.9441, 2.3363, 0.9289, 1.6615, 1.1726, 1.8066, 2.149, 1.983]

syserror = None

Restricting the data¶

Trying to fit the whole data set will fail because the first data

point has an error of 0, so it is necessary to

restrict, or filter out,

this data point. The simplest way is to select a data range to ignore using

ignore(), in this

case everything where \(x < 1\):

>>> d.get_filter()

'0.0000:20.0000'

>>> d.ignore(None, 1)

>>> d.get_filter()

'2.0000:20.0000'

The get_filter() routine returns a

text description of the filters applied to the data; it starts

with all the data being included (0 to 20) and then after

excluding all points less than 1 the filter is now 2 to 20.

The format can be changed to something more appropriate for

this data set:

>>> d.get_filter(format='%d')

'2:20'

Creating the model¶

Table 5 lists the model fit to this dataset as

which can be constructed from components using the

Const1D

and Exp models, as shown below:

>>> from sherpa.models.basic import Const1D, Exp

>>> plateau = Const1D('plateau')

>>> rise = Exp('rise')

>>> mdl = plateau / (1 + rise)

>>> print(mdl)

(plateau / (1 + rise))

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

plateau.c0 thawed 1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.offset thawed 0 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.coeff thawed -1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.ampl thawed 1 0 3.40282e+38

The amplitude of the exponential is fixed at 1, but the other

terms will remain free in the fit, with plateau.c0 representing

the normalization, and the rise.offset and rise.coeff terms

the exponent term. The offset and coeff terms do not

match the form used in the paper, namely \(a + b t\),

which has some interesting consequences for the fit, as will

be discussed below in the

user-model section.

>>> rise.ampl.freeze()

>>> print(mdl)

(plateau / (1 + rise))

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

plateau.c0 thawed 1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.offset thawed 0 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.coeff thawed -1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.ampl frozen 1 0 3.40282e+38

The funtional form of the exponential model provided by Sherpa, assuming an amplitude of unity, is

which means that I expect the final values to be \({\rm coeff} \simeq -0.5\) and, as \(- {\rm coeff} * {\rm offset} \simeq 1.9\), then \({\rm offset} \simeq 4\). The plateau value should be close to 15.

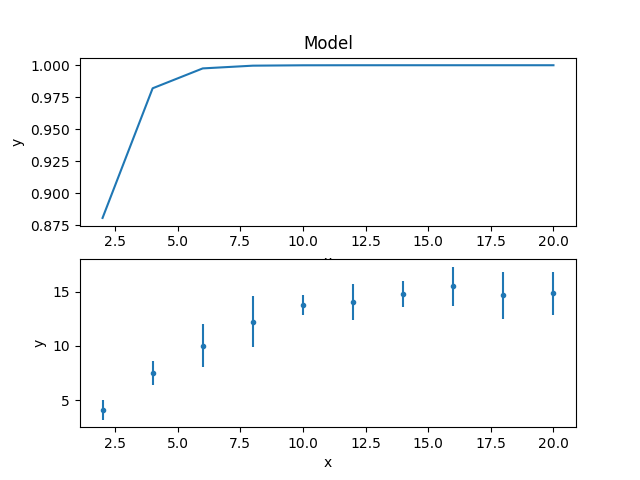

The model and data can be shown together, but as the fit has not yet been made then showing on the same plot is not very instructive, so here’s two plots one above the other, created by mixing the Sherpa and Matplotlib APIs:

>>> from sherpa.plot import ModelPlot

>>> mplot = ModelPlot()

>>> mplot.prepare(d, mdl)

>>> plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

>>> mplot.plot(clearwindow=True)

>>> plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

>>> dplot.plot(clearwindow=True)

>>> plt.title('')

The title of the data plot was removed since it overlaped the X axis of the model plot above it.

Fitting the data¶

The main difference to fitting the first example is that the

Chi2 statistic is used,

since the data contains error values.

>>> from sherpa.stats import Chi2

>>> from sherpa.fit import Fit

>>> f = Fit(d, mdl, stat=Chi2())

>>> print(f)

data = NaNO_3

model = (plateau / (1 + rise))

stat = Chi2

method = LevMar

estmethod = Covariance

>>> print("Starting statistic: {}".format(f.calc_stat()))

Starting statistic: 633.2233812020354

The use of a Chi-square statistic means that the fit also calculates the reduced statistic (the final statistic value divided by the degrees of freedom), which should be \(\sim 1\) for a “good” fit, and an estimate of the probability (Q value) that the fit is good (this is also based on the statistic and number of degrees of freedom).

>>> fitres = f.fit()

>>> print(fitres.format())

Method = levmar

Statistic = chi2

Initial fit statistic = 633.223

Final fit statistic = 101.362 at function evaluation 17

Data points = 10

Degrees of freedom = 7

Probability [Q-value] = 5.64518e-19

Reduced statistic = 14.4802

Change in statistic = 531.862

plateau.c0 10.8792

rise.offset 457.221

rise.coeff 24.3662

The reduced chi-square value is large, as shown in the screen output above and the explicit access below, the probability value is essentially 0, and the parameters are nowhere near the expected values.

>>> print("Reduced chi square = {:.2f}".format(fitres.rstat))

Reduced chi square = 14.48

Visually comparing the model and data values highlights how poor this fit is:

>>> mplot.prepare(d, mdl)

>>> dplot.plot()

>>> mplot.overplot()

Either the model has got caught in a local minimum, or it is not

a good description of the data. To investigate further, a useful technique

is to switch the optimiser and re-fit; the hope is that the different

optimiser will be able to escape the local minima in the search

space. The default optimiser used by

Fit is

LevMar, which is often a good

choice for data with errors. The other standard optimiser

provided by Sherpa is

NelderMead, which is often slower

than LevMar - as it requires more model evaluations - but

less-likely to get stuck:

>>> from sherpa.optmethods import NelderMead

>>> f.method = NelderMead()

>>> fitres2 = f.fit()

>>> print(mdl)

(plateau / (1 + rise))

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

plateau.c0 thawed 10.8792 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.offset thawed 457.221 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.coeff thawed 24.3662 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.ampl frozen 1 0 3.40282e+38

An alternative to replacing the

method attribute, as done above, would be

to create a new Fit object - changing the

method using the method attribute of the initializer, and use

that to fit the model and data.

As can be seen, the parameter values have not changed; the

dstatval attribute contains the

change in the statsitic value, and as shown below, it has

not improved:

>>> fitres2.dstatval

0.0

The failure of this fit is actually down to the coupling of

the offset and coeff parameters of the

Exp model, as will be

discussed below,

but a good solution can be found by tweaking the starting

parameter values.

Restarting the fit¶

The reset() will change the

parameter values back to the

last values you set them to,

which may not be the same as their

default settings

(in this case the difference is in the state of the rise.ampl

parameter, which has remained frozen):

>>> mdl.reset()

>>> print(mdl)

(plateau / (1 + rise))

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

plateau.c0 thawed 1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.offset thawed 0 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.coeff thawed -1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise.ampl frozen 1 0 3.40282e+38

Note

It is not always necessary to reset the parameter values when trying to get out of a local minimum, but it can be a useful strategy to avoid getting trapped in the same area.

One of the simplest changes to make here is to set the plateau term to the maximum data value, as the intention is for this term to represent the asymptote of the curve.

>>> plateau.c0 = np.max(d.y)

>>> mplot.prepare(d, mdl)

>>> dplot.plot()

>>> mplot.overplot()

A new fit object could be created, but it is also possible

to re-use the existing object. This leaves the optimiser set to

NelderMead, although in this

case the same parameter values are found if the method

attribute had been changed back to

LevMar:

>>> fitres3 = f.fit()

>>> print(fitres3.format())

Method = neldermead

Statistic = chi2

Initial fit statistic = 168.42

Final fit statistic = 0.299738 at function evaluation 42

Data points = 10

Degrees of freedom = 7

Probability [Q-value] = 0.9999

Reduced statistic = 0.0428198

Change in statistic = 168.12

plateau.c0 14.9694

rise.offset 4.17729

rise.coeff -0.420696

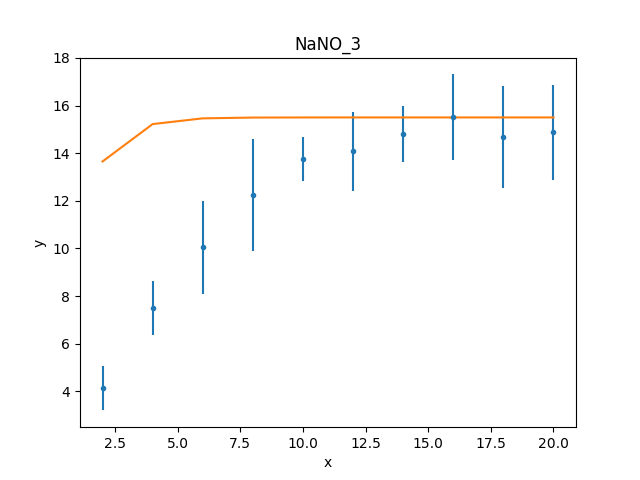

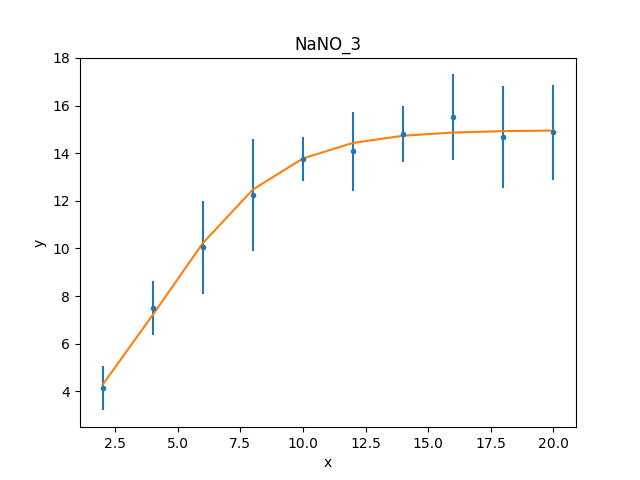

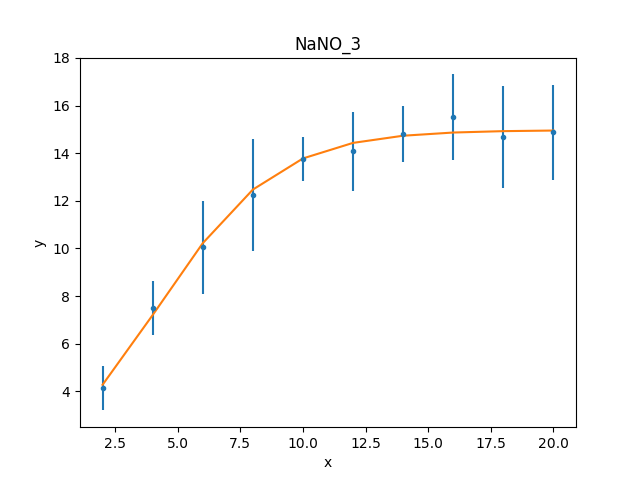

These results already look a lot better than the previous attempt; the reduced statistic is much smaller, and the values are similar to the reported values. As shown in the plot below, the model also well describes the data:

>>> mplot.prepare(d, mplot)

>>> dplot.plot()

>>> mplot.overplot()

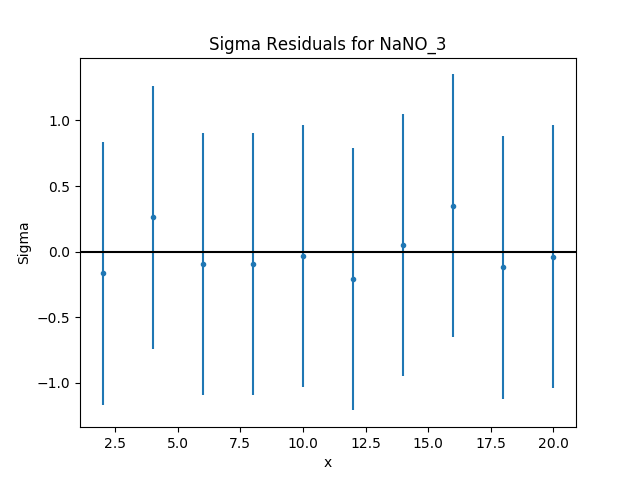

The residuals can also be displayed, in this case normalizing by

the error values by using a

DelchiPlot plot:

>>> from sherpa.plot import DelchiPlot

>>> residplot = DelchiPlot()

>>> residplot.prepare(d, mdl, f.stat)

>>> residplot.plot()

>>> residplot.hline(0, overplot=True, linecolor='black')

Unlike the data and model plots, the

prepare() method of the

residual plot requires a statistic object, so the value

in the fit object (using the stat

attribute) is used.

Given that the reduced statistic for the fit is a lot smaller

than 1 (\(\sim 0.04\)), the residuals are all close to 0:

the ordinate axis shows \((d - m) / e\) where

\(d\), \(m\), and \(e\) are data, model, and

error value respectively, and the

hline() method was used to

draw a line at \({\rm sigma} = 0\).

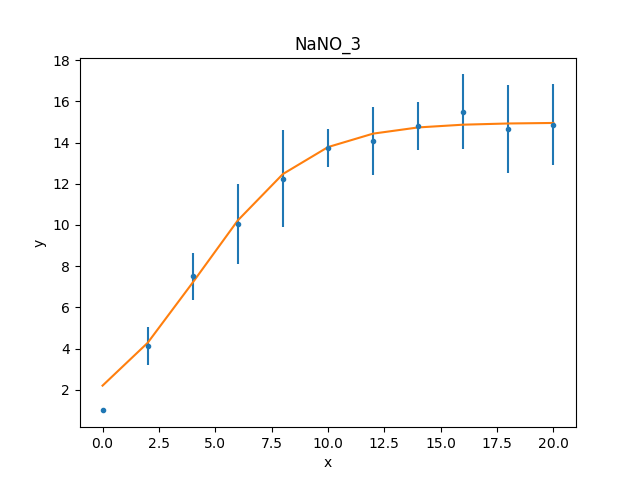

What happens at \(t = 0\)?¶

The filtering applied earlier

can be removed, to see how the model behaves at low times. Calling

the notice() without any arguments

removes any previous filter:

>>> d.notice()

>>> d.get_filter(format='%d')

'0:20'

For this plot, the FitPlot class is going

to be used to show both the data and model rather than doing it

manually as above:

>>> from sherp.plot import FitPlot

>>> fitplot = FitPlot()

>>> dplot.prepare(d)

>>> mplot.prepare(d, mdl)

>>> fitplot.prepare(dplot, mplot)

>>> fitplot.plot()

Note

The prepare method on the

components of the Fit plot (in this case dplot and

mplot) must be called with their appropriate arguments

to ensure that the latest changes - such as filters and

parameter values - are picked up.

Warning

Trying to create a residual plot for this new data range,

will end up with a division-by-zero error from the

prepare call, as the first data point has an error

of 0 and the residual plot shows \((d - m) / e\).

For the rest of this example the first data point has to be removed:

>>> d.ignore(None, 1)

Estimating parameter errors¶

The calc_stat_info() method returns

an overview of the current fit:

>>> statinfo = f.calc_stat_info()

>>> print(statinfo)

name =

ids = None

bkg_ids = None

statname = chi2

statval = 0.2997382864907501

numpoints = 10

dof = 7

qval = 0.999900257643

rstat = 0.04281975521296431

It is another way of getting at some of the information in the

FitResults object; for instance

>>> statinfo.rstat == fitres3.rstat

True

Note

The FitResults object refers to the model at the time

the fit was made, whereas calc_stat_info is calculated

based on the current values, and so the results can be

different.

The est_errors() method is used to

estimate error ranges for the parameter values. It does this by

varying the parameters around the best-fit location

until the statistic value has increased by a set amount.

The default method for estimating errors is

Covariance

>>> f.estmethod.name

'covariance'

which has the benefit of being fast, but may not be as robust as other techniques.

>>> coverrs = f.est_errors()

>>> print(coverrs.format())

Confidence Method = covariance

Iterative Fit Method = None

Fitting Method = levmar

Statistic = chi2

covariance 1-sigma (68.2689%) bounds:

Param Best-Fit Lower Bound Upper Bound

----- -------- ----------- -----------

plateau.c0 14.9694 -0.880442 0.880442

rise.offset 4.17729 -0.646012 0.646012

rise.coeff -0.420696 -0.12247 0.12247

As shown below,

the error values can be extracted from the output of

est_errors().

The default is to calculate “one sigma” error bounds

(i.e. those that cover 68.3% of the expected parameter range),

but this can be changed by altering the

sigma attribute

of the error estimator.

>>> f.estmethod.sigma

1

Changing this value to 1.6 means that the errors are close to the 90% bounds:

>>> f.estmethod.sigma = 1.6

>>> coverrs90 = f.est_errors()

>>> print(coverrs90.format())

Confidence Method = covariance

Iterative Fit Method = None

Fitting Method = neldermead

Statistic = chi2

covariance 1.6-sigma (89.0401%) bounds:

Param Best-Fit Lower Bound Upper Bound

----- -------- ----------- -----------

plateau.c0 14.9694 -1.42193 1.42193

rise.offset 4.17729 -1.04216 1.04216

rise.coeff -0.420696 -0.19679 0.19679

The covariance method uses the covariance matrix to estimate

the error surface, and so the parameter errors are symmetric.

A more-robust, but often significantly-slower, approach is to

use the Confidence approach:

>>> from sherpa.estmethods import Confidence

>>> f.estmethod = Confidence()

>>> conferrs = f.est_errors()

plateau.c0 lower bound: -0.804259

rise.offset lower bound: -0.590258

rise.coeff lower bound: -0.148887

rise.offset upper bound: 0.714407

plateau.c0 upper bound: 0.989664

rise.coeff upper bound: 0.103391

The error estimation for the confidence technique is run in parallel - if the machine has multiple cores usable by the Python multiprocessing module - which can mean that the screen output above is not always in the same order. As shown below, the confidence-derived error bounds are similar to the covariance bounds, but are not symmetric.

>>> print(conferrs.format())

Confidence Method = confidence

Iterative Fit Method = None

Fitting Method = neldermead

Statistic = chi2

confidence 1-sigma (68.2689%) bounds:

Param Best-Fit Lower Bound Upper Bound

----- -------- ----------- -----------

plateau.c0 14.9694 -0.804259 0.989664

rise.offset 4.17729 -0.590258 0.714407

rise.coeff -0.420696 -0.148887 0.103391

The default is to use all

thawed parameters

in the error analysis, but the est_errors()

method has a parlist attribute which can be used to restrict

the parameters used, for example to just the offset term:

>>> offseterrs = f.est_errors(parlist=(mdl.pars[1], ))

rise.offset lower bound: -0.590258

rise.offset upper bound: 0.714407

>>> print(offseterrs)

datasets = None

methodname = confidence

iterfitname = none

fitname = neldermead

statname = chi2

sigma = 1

percent = 68.2689492137

parnames = ('rise.offset',)

parvals = (4.177287700807689,)

parmins = (-0.59025803525842369,)

parmaxes = (0.71440700826435144,)

nfits = 8

The covariance and confidence limits can be compared by

accessing the fields of the

ErrorEstResults object:

>>> fmt = "{:13s} covar=±{:4.2f} conf={:+5.2f} {:+5.2f}"

>>> for i in range(len(conferrs.parnames)):

... print(fmt.format(conferrs.parnames[i], coverrs.parmaxes[i], \

... conferrs.parmins[i], conferrs.parmaxes[i]))

...

plateau.c0 covar=±0.88 conf=-0.80 +0.99

rise.offset covar=±0.65 conf=-0.59 +0.71

rise.coeff covar=±0.12 conf=-0.15 +0.10

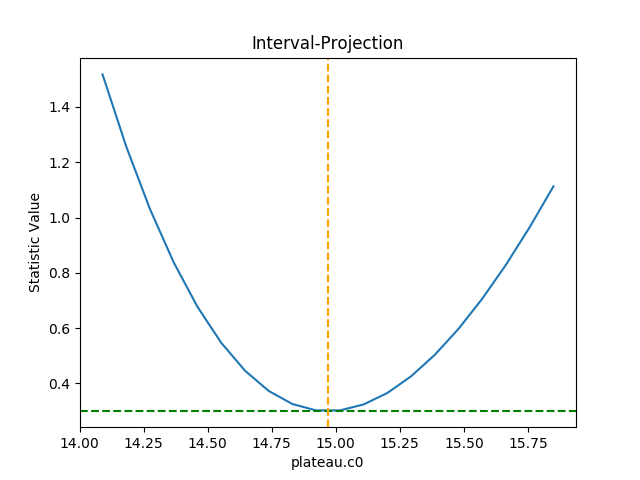

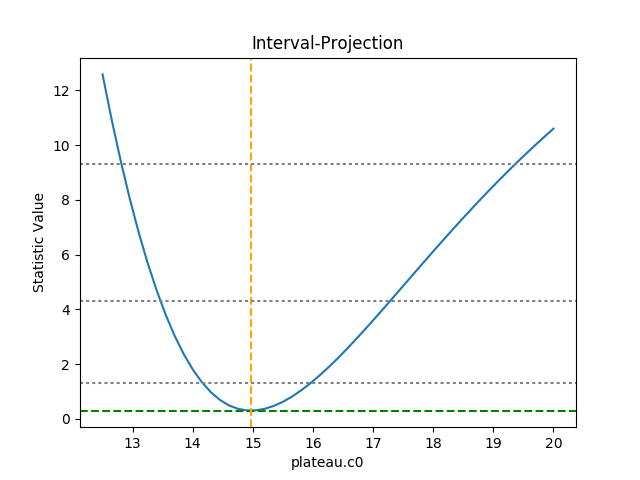

The est_errors() method returns a

range, but often it is important to visualize the error

surface, which can be done using the interval projection

(for one parameter) and region projection (for two parameter)

routines. The one-dimensional version is created with the

IntervalProjection

class, as shown in the following, which shows how the statistic

varies with the plateau term (the vertical dashed line indicates

the best-fit location for the parameter, and the horizontal

line the statistic value for the best-fit location):

>>> from sherpa.plot import IntervalProjection

>>> intproj = IntervalProjection()

>>> intproj.calc(f, plateau.c0)

>>> intproj.plot()

Unlike the previous plots, this requires calling the

calc() method

before plot(). As

the prepare()

method was not called, it used the default options to

calculate the plot range (i.e. the range over which

plateau.c0 would be varied), which turns out in this

case to be close to the one-sigma limits.

The range, and number of points, can also be set explicitly:

>>> intproj.prepare(min=12.5, max=20, nloop=51)

>>> intproj.calc(f, plateau.c0)

>>> intproj.plot()

>>> s0 = f.calc_stat()

>>> for ds in [1, 4, 9]:

... intproj.hline(s0 + ds, overplot=True, linestyle='dot', linecolor='gray')

...

The horizontal lines indicate the statistic value for one, two, and three sigma limits for a single parameter value (and assuming a Chi-square statistic). The plot shows how, as the parameter moves away from its best-fit location, the search space becomes less symmetric.

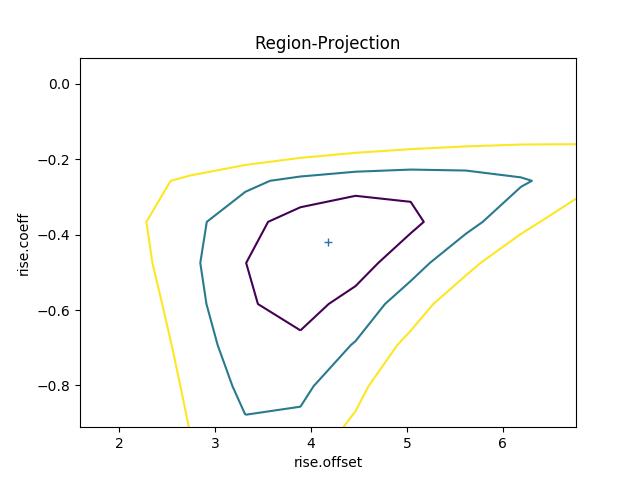

Following the same approach, the RegionProjection

class calculates the statistic value as two parameters are varied,

displaying the results as a contour plot. It requires two parameters

and the visualization is

created with the contour()

method:

>>> from sherpa.plot import RegionProjection

>>> regproj = RegionProjection()

>>> regproj.calc(f, rise.offset, rise.coeff)

>>> regproj.contour()

The contours show the one, two, and three sigma contours, with the

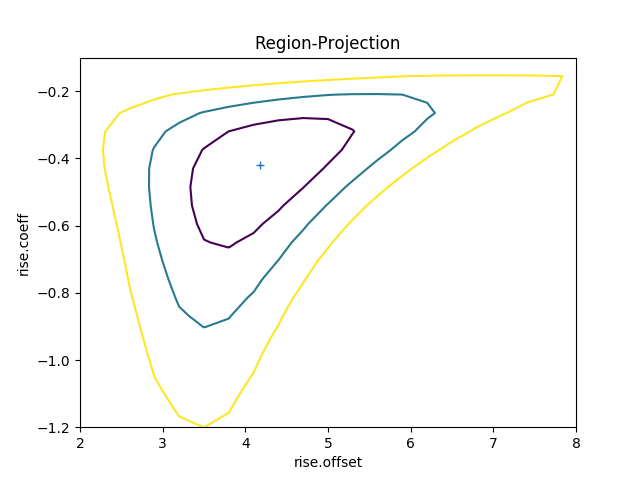

cross indicating the best-fit value. As with the interval-projection plot,

the prepare() method can

be used to define the grid of points to use; the values below are

chosen to try and cover the full three-sigma range as well as improve

the smoothness of the contours by increasing the number of points

that are looped over:

>>> regproj.prepare(min=(2, -1.2), max=(8, -0.1), nloop=(21, 21))

>>> regproj.calc(f, rise.offset, rise.coeff)

>>> regproj.contour()

Writing your own model¶

The approach above has provided fit results, but they do not match those of the paper and, since

it is hard to transform the values from above to get

accurate results. An alternative approach is to

create a model with the parameters

in the required form, which requires a small amount

of code (by using the

Exp class to do the actual

model evaluation).

The following class (MyExp) creates a model that has

two parameters (a and b) that represents

\(f(x) = e^{a + b x}\). The starting values for these

parameters are chosen to match the default values of the

Exp parameters,

where \({\rm coeff} = -1\) and \({\rm offset} = 0\):

class MyExp(ArithmeticModel):

"""A simpler form of the Exp model.

The model is f(x) = exp(a + b * x).

"""

def __init__(self, name='myexp'):

self.a = Parameter(name, 'a', 0)

self.b = Parameter(name, 'b', -1)

# The _exp instance is used to perform the model calculation,

# as shown in the calc method.

self._exp = Exp('hidden')

return ArithmeticModel.__init__(self, name, (self.a, self.b))

def calc(self, pars, *args, **kwargs):

"""Calculate the model"""

# Tell the exp model to evaluate the model, after converting

# the parameter values to the required form, and order, of:

# offset, coeff, ampl.

#

coeff = pars[1]

offset = -1 * pars[0] / coeff

ampl = 1.0

return self._exp.calc([offset, coeff, ampl], *args, **kwargs)

This can be used as any other Sherpa model:

>>> plateau2 = Const1D('plateau2')

>>> rise2 = MyExp('rise2')

>>> mdl2 = plateau2 / (1 + rise2)

>>> print(mdl)

(plateau2 / (1 + rise2))

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

plateau2.c0 thawed 1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise2.a thawed 0 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

rise2.b thawed -1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

>>> fit2 = Fit(d, mdl2, stat=Chi2())

>>> res2 = fit2.fit()

>>> print(res2.format())

Method = levmar

Statistic = chi2

Initial fit statistic = 633.223

Final fit statistic = 0.299738 at function evaluation 52

Data points = 10

Degrees of freedom = 7

Probability [Q-value] = 0.9999

Reduced statistic = 0.0428198

Change in statistic = 632.924

plateau2.c0 14.9694

rise2.a 1.75734

rise2.b -0.420685

>>> dplot.prepare(d)

>>> mplot2 = ModelPlot()

>>> mplot2.prepare(d, mdl2)

>>> dplot.plot()

>>> mplot2.overplot()

Unlike the initial attempt,

this version did not require any manual intervention to find the

best-fit solution. This is because the degeneracy between the two

terms of the exponential in the

Exp model have been broken in

this version, and so the optimiser work better.

It also has the advantage that the parameters match the

problem, and so the parameter limits determined below can be

used directly, without having to transform them.

>>> fit2.estmethod = Confidence()

>>> conferrs2 = fit2.est_errors()

plateau2.c0 lower bound: -0.804444

rise2.b lower bound: -0.148899

rise2.a lower bound: -0.38086

rise2.b upper bound: 0.10338

plateau2.c0 upper bound: 0.989623

rise2.a upper bound: 0.489919

>>> print(fit2.conferrs2.format())

Confidence Method = confidence

Iterative Fit Method = None

Fitting Method = levmar

Statistic = chi2

confidence 1-sigma (68.2689%) bounds:

Param Best-Fit Lower Bound Upper Bound

----- -------- ----------- -----------

plateau2.c0 14.9694 -0.804444 0.989623

rise2.a 1.75734 -0.38086 0.489919

rise2.b -0.420685 -0.148899 0.10338

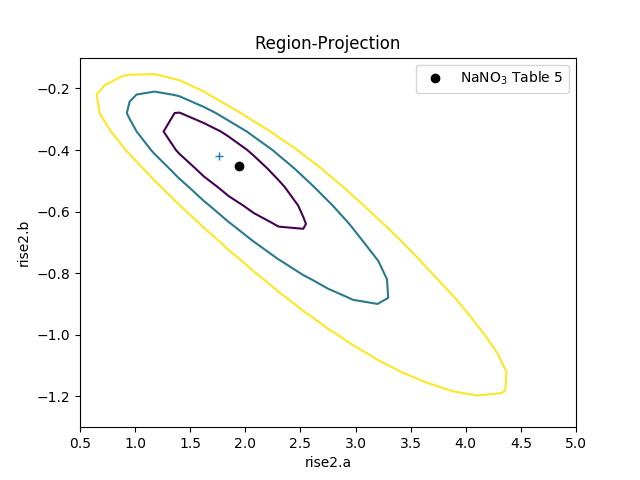

The difference in the model parameterisation can also be seen in the various error-analysis plots, such as the region-projection contour plot (where the limits have been chosen to cover the three-sigma contour), and a marker has been added to show the result listed in Table 5 of Zhao et al:

>>> regproj2 = RegionProjection()

>>> regproj2.prepare(min=(0.5, -1.2), max=(5, -0.1), nloop=(21, 21))

>>> regproj2.calc(fit2, rise2.a, rise2.b)

>>> regproj2.contour()

>>> plt.plot(1.941, -0.453, 'ko', label='NaNO$_3$ Table 5')

>>> plt.legend(loc=1)