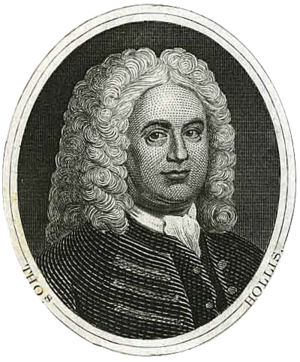

John Winthrop the Younger (1608-1676). He is described as America's first astronomer. Around 1660 he buys a ten foot telescope somewhere in Europe, which he brings back to Cambridge. It apparently pretty much sucks, not even being able to resolve Saturn.

So in 1663, he travels back to Europe and returns with a telescope that's smaller, but I can only assume better: "3 foote & halfe wth a concave ey-glasse".nescopes

In 1665 he uses his telescope to discover Jupiter's fifth moon. Except it turned out to be just a star in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In 1672 he gives his 3.5 foot telescope to Harvard, which seems to be Harvard's first telescope.nescopes heavensalarm

Don't be deceived by portraits of a John Winthrop with a telescope who is a well-known astronomer. That image is a painting of John Winthrop the Elder's great-great grandson, or the great grandson of this John Winthrop.

The artist for this portrait is apparently unknown, as is the year that it was painted. Still, Harvard considers it to be a valid portrait.winthropportrait

Earliest source: "Thomas Hollis (1659–1731)." Wikipedia. Wikipedia, 28 July 2015.wikihollis

In 1722, Thomas Hollis (1659-1731) donated a 24-foot telescope to Harvard College.winthropfirst It was housed in Massachusetts Hall. Later moved to Harvard Hall, where it, and all but one of Harvard's other telescopes were destroyed in a fire in 1764.firstfour(missing)

Thomas Hollis established the Hollis Professorship of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy in 1727, an important position for the growth of Harvard's science programs including in particular astronomy. This was the second Hollis professorship established, the first being the Hollis Professorship of Divinity, a controversial donation promoting the Baptist movement.sketchhist

This image is from an 1854 bank note from Holliston Savings Bank in Holliston Massachusetts. Holliston was named after Thomas Hollis. His image appeared on the one, two, five, and ten dollar bank notes from Holliston Bank.banknotes Apparently this is based on a painting by John Copley, which is based in turn on another painting by Giovanni Battista Cipriani in 1764, which was a copy of a painting by an unknown artist in 1723 (while Hollis was actually alive).

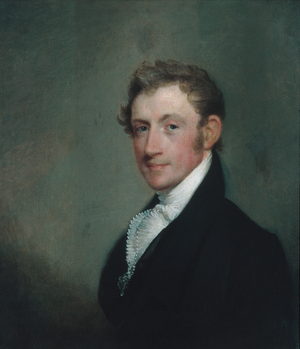

Image Credit: Gilbert Stuart

David Sears, 1815

Painting of philanthropist David Sears by Gilbert Stuart. Twenty eight years after this painting, David Sears will become the driving force in the donation campaign that builds Harvard Observatory and buys the Great Refractor. He makes two separate $5000 donations (about $150,000 2015 dollars).

The stone building that houses the Great Refractor is named the "Sears Tower" after him.

(Gilbert Stuart is a well-known portrait painter. His most famous work is an unfinished painting of George Washington, which was used as the basis for the one dollar bill. He did manage to complete several other portraits of George Washington, as well as John Adams, Abigail Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams, who also plays a pivotal role in our little story.)

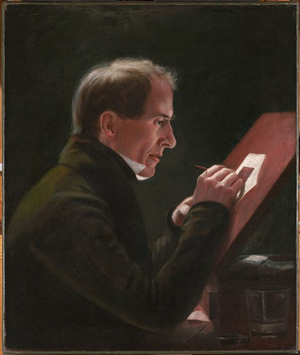

Image Credit: George Hollingsworth

Earliest source: "Alvan Clark (1804-1887)." Harvard Portrait/Clock Collections. Harvard Libraries, HUAM311226

Alvan Clark (1804-1887), who at the time of this portrait is a portrait painter himself (shown here painting), specializing in miniatures. He is also an engraver. In the early 1840s he and his sons Alvan Graham and George Basset Clark go into telescope making business as a part-time endeavor.

Sometime shortly after the Great Refractor is installed (1847), Alvan Clark has the opportunity to use the instrument. Based on his telescope-making experience so far, he sees subtle flaws. As the story goes, this experience, along with hearing how much money could be made selling large refractors ($12,000 for Harvard's lens or about $300,000 in 2015 dollars), motivates him to go into telescope-making full time, and take on more ambitious projects. By 1862, they build the largest refractor in the world (18.5"), originally commissioned for the University of Mississippi, but sold to the University of Chicago, due to the Civil War.

The Clarks would go on to make the world's largest refractor four more times, including the 36 inch Lick refractor, and finally the 40 inch Yerkes refractor, the largest working refractor ever built.

While the relationship with Harvard is fairly tangential (and geographic, as their business was located in Cambridge for years, see the map of 1877 below), this portrait is actually currently located at the Observatory. According to Harvard, it was a gift of Mrs. Alvan Clark [which one?] to the Harvard College Observatory in 1899 (Alvan died in 1887, Alvan G. died in 1897).

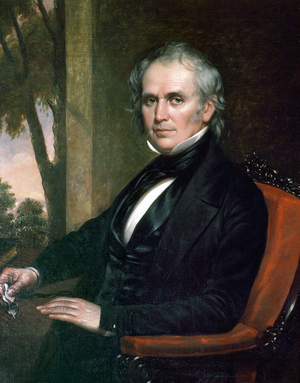

Image Credit: Cephas Thompson

Earliest source: "William Cranch Bond." Time and Navigation / The untold story of getting from here to there.. Smithsonian Institution, 19 [retrieved] August 2015.sibond

This is the earliest depiction I have of William Cranch Bond. Bond was a famous clockmaker, by virtue of being the son of a famous clockmaker. He was also keenly interested in astronomy from an early age. As a child, he used a telescope to observe a solar eclipse, apparently without supervision, and damaged his eyesight for a number of years.bondmemorials. His fascination with astronomy was such that in 1815, John Farrar, then the Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, asked him to visit observatories in Europe and report back. Apparently Bond's descriptions sounded too expensive, and no Observatory was built at tha time.heavensalarm

Evenutally though, the Observatory was created, and Harvard "hired" him as the first director of their new Observatory. Hiring did not involve any salary, but it did involve him transferring all of his own personal astronomical equipment to Harvard property. Not a bad deal for Harvard.

Earliest source: William Cranch Bond and George PHillips Bond [and Joseph Winlock]. Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College / 1859-1860 vol. 7. Welch, Bigelow, & Co., 1872.annals7

A photo of William Cranch Bond. Bond died in 1859, while negative photography was still relatively new, but a negative of him must have existed in order to print this image, which is taken from the 1872 Annals.annals7 I'm unsure of the printing technology used here. At first I assumed it was a photolithograph, however no halftone screen is visible (although it could be a gravure method). This could also be a photo pasted into each copy, probably an albumen print, although I don't see all the edges if it's pasted - which could be a scan quality issue.

This is only the second image of him I'm aware of, the first being the painting above. All other images I've seeen are versions of one of these two original sources. The 1855 date given here is a fairly wild guess of when the photograph that it was based on was taken.

It's a fairly early example of a printed photograph, but not crazy early. Photographs in print didn't really become common until 1880s or especially 1890s, but photographs had been in print experimentally since about 1835, and to a limited degree in professional publishing since the early 1850s.

Crazy hair, right? I think some of the images derived from this original take a little artistic license, and make it even a bit more wild. I haven't had time to research his hair, but it's definitely an avenue of exploration. Was this fashionable? Unfashionable? Mad-scientist? Did people mention his hair in the published memorials of him? So many important questions remain.

Oh the irony.

The second director of the Observatory, taking over after his father's death in 1859, George Phillips Bond will serve as director for only six years, until his own death. He is considered the father of astrophotography, dedicating his short career to progress in this area. He and his father assisted John Whipple in his famous photographs of the moon, and it was George who brought them to Europe, where they were instantly famous. The heavily photographic programs of future directors Winlock and Pickering (with all the women computers doing the grunt work) will be built on foundations created by George Phillips Bond.

And despite all this, there are no known photographs of him at all, nor any portraits of any kind.

All we have is descriptions. His daughter Elizabeth offers hers:

"In person he was rather tall (a little under six feet) and slender, becoming, of later yearsm painfully thin. His hair was wavy and very dark, if not black; his complexion pale, and his eyes of the deepest blue, with a glowing spiritual light in them that transfigured the worn face, lending it a singular power and beauty quite apart from mere regularity of feature."bondmemorials

He was not the son destined to follow in his father's footsteps. His younger brother, William Cranch Bond Jr. was an avid astronmer and seen by some as the bright hope for the future of the Observatory. But he died at the end of his college career. Older brother George assumed the mantle of astronomy "with some reluctance" as a friend describes. George's first and greatest love was ornithology.bondmemorials

As if having no portraits isn't enough of a slight, it's also hard to find him now. Some online sources say he is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery as is his father. But he's not in the Mount Auburn Database. So I had a look for myself. The family Bond monument has many names carved in it. George's name and other details are carved into the back, behind the bushes. But it turns out that many family names have been added to W. C. Bond's monument, though they are interred elsewhere. After contacting Mount Auburn Cemetery, they were able to tell me that George is interred in Cambridge Cemetery, lot 305.

Earliest source: F. O. Vaille and H. A. Clark (Class of 1874). The Harvard Book / A Series of Historical, Biographical, and Descriptive Sketches vol. 1. Welch, Bigelow, and Company, 1875.harvardbook

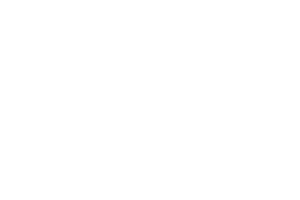

Joseph Winlock was the third director of the Harvard Observatory, taking over after George Phillips Bond passed away in 1865. Winlock would only serve a decade until his own death, around the time this book was published.

Winlock was the grandson of a revolutionary war soldier, General Joseph Winlock (starting as a private; Captain by the end of the war). Raised on a farm in Kentucky, he graduated from Shelby College, where he was given an appointment as professor of Mathematics and Astronomy. He moved from there to working as a computer in Cambridge for the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac. After several more job changes and advancements, he wound up at the Observtory, where he took over as director.academywinlock

Under Winlock, the Observatory sold accurate time data to various customers, in part based on improvements to the instruments made by Winlock. In appreciation for this, Harvard provided his family with a stipend of the proceeds from this service for five years. Perhaps it was not enough, or perhaps she just wanted to follow in her father's footsteps, because his daughter Anna felt the need to ask the Observatory for a job as a computer, and thus became the first woman hired for this work at the Observatory (as far as anyone knows), eventually joined by her sister Louisa.

I don't know when the photograph was taken, but given that all the photographs in the book seem to be in the same style, I think it's ok to assume they were all taken in preparation for this book, which was begun by the class of 1874 in their final year.harvardbook

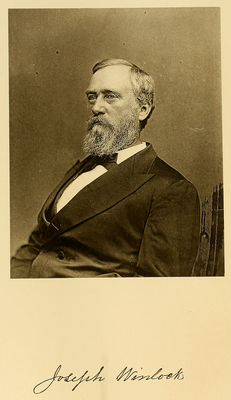

An 1877 map of Cambridge, notable because of all the hand drawn buildings of Cambridge. The Observatory is shown with both wings, with the Prime Vertical building to the north, and with the additional space completed to the North West. It also shows several smaller buildings to the west, but I believe these are houses off of Madison, as they don't correspond to the instruments that the Observatory had in place at the time. Substantial tree growth is shown in what was earlier mostly cleared fields. The Botanical Garden used Observatory space as a nursery at some point, although I'm not sure how much this contributed to the landscaping.

If you inspect the bottom right portion of the map, and follow the bridge up from the bottom, taking the left branch, this will put you on Brookline Steet. As you go up you will first cross Leverett St. and then come to Henry Street. There are several buildings drawn in below and to the right of Brookline and Henry. This is the Alvan Clark & Sons telescope company. For more details, see the 1840 portrait of Alvan Clark above.

The same year this map was made, Alvan Clark used a 26-inch telescope he'd made for the University of Virginia to confirm the discovery of Mars' moons, made by the other 26-inch telescope at the Naval Observatory, which Clark & Sons had delivered several years earlier.academy12 mechanic26

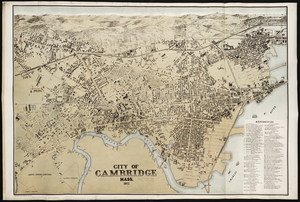

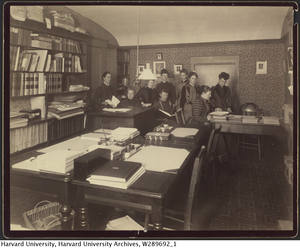

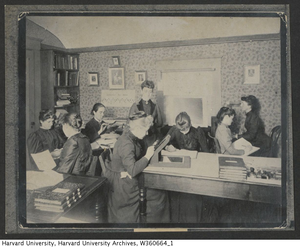

Earliest source: "[Observatory women computers], 1891." Harvard University Archives / HUV 1210 (9-3). Harvard Libraries, olvwork289691

A group photo of computers at Harvard together with Mary Anna Palmer Draper, aka Mrs. Henry Draper. She's seated in the middle. After her husband's death, she contributed a significant sum of money to continue her late husbands' dream of scientific astrophotograpy, leading to the Draper Catalog, an ambitious project of the Observatory. Many, though not all, computers were funded for this project.

Harvard dates this as 1891. It seems to be approximately the same time as other photos with similar groups of women, taken in the same room. I think there were two pairs of photos taken on different days.

The photo was taken in the long computing room (see 1876 floor plans) on the south side of the second floor (the top floor, excluding the dome) of the building. The photograph was taken facing east, and the doorway in the photo is the closet shown in the floor plan.

Left to right:

Note that Stevens is Mrs. Fleming's maiden name, and she did have other relatives in Boston, but so far I don't know if any of the other Stevens that worked at the Observatary are related.

[Observatory women computers], 1891

1891

General: The women depicted in this photograph analyized stellar photographs and computed data at the Harvard College Observatory.

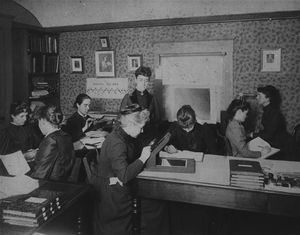

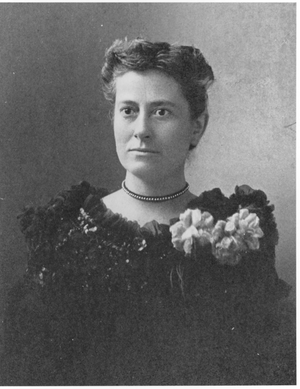

Earliest source: "Observatory girls with Mrs. Draper, 1891

Alternate Title: [Observatory computer room and staff], 1891." Harvard University Archives / HUV 1210 (9-5). Harvard Libraries, olvwork289692

Another photograph taken in the same place and on the same day as the previous, with the same people.

Computers in one of the computing rooms at the Observatory. Harvard's date of 1891 for this photo is probably pretty accurate. It has to be after Dec. 1889, based on the graph on the wall of β Aurigӕ, just behind Antonia Maury (who is credited for discovering that it is a binary star). And as it was published in an April 1892 New England Magazine, thta's the upper limit on the photo.

This is the same location as the photos with Mrs. Draper and some of the computers, the larger computing room on the top floor of the west wing of the Observatory.

From left to right:

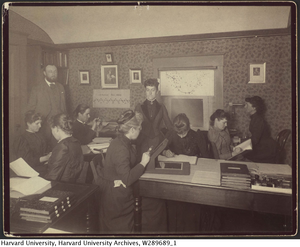

Earliest source: "[Observatory computer room and staff], 1891." Harvard University Archives / HUV 1210 (9-4). Harvard Libraries, olvwork289689

Nearly the identical photo as the previous, but with Pickering added standing on the left. Obviously taken the same day.

Note that the women did not work this closely. As can be seen in the above photos with Mrs. Draper, the room is larger and they are crowded together for sake of the photograph. There were between three and five rooms total for the computing work, and by my best guess about 15 women worked there at that time, as well as at least five men. Still cramped, but not this cramped.

The following year, a brick building was constructed to help out with the space issues.

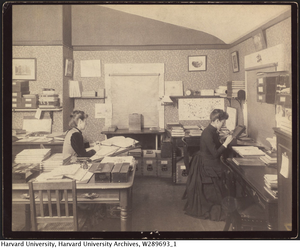

Earliest source: "Observatory [analysis of stellar spectra], 1891." Harvard University Archives / HUV 1210 (9-6). Harvard Libraries, olvwork289693

Date is from Harvard

I think this is Williamina Fleming, seated on the right. The woman on the left may be Mabel C. Stevens, and she's wearing the same dress as one of the women of women computers in the old building with Fleming. Fleming appears to be wearing the same dress also, but without the jacket.

This photo was taken on the same floor as that other photo, but in a the other computer room at the oppisite side of the building.

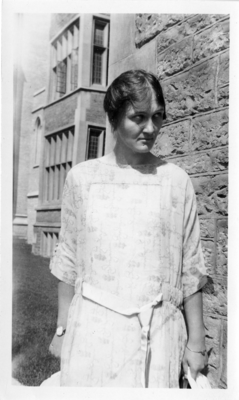

Earliest source: "Portrait of Annie Jump Cannon." Radcliffe College Archives / PC 70-1-2. Harvard Libraries, olvwork353777

The earliest image I've found so far of Annie Jump Cannon. This is what Harvard says: "Inscription: Verso: Miss Annie Jump Cannon of the Harvard observatory, taken while doing graduate work at Radcliffe College", and dates it 1895-1897. This would put her at about 33 years old. She had taken ten years off for lack of available work between Wellesley and Radcliffe. During this she took up photography, published a small book of photographsfootsteps, caught scarlet fever, and lost most of her hearing.wikicannon

I have a small suspicion based on her appearance in other photos that this photo may be much earlier than Harvard's 1896 date, but so far nothing to back it up.

Use/Copyright: Radcliffe College Archives: This image may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the Radcliffe Archives.

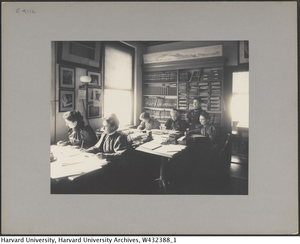

Earliest source: "[Observatory data analysis by women computers] ." Harvard University Archives / UAV 630.271 (E4116). Harvard Libraries, olvwork432388

Women computers working (or posing as if they're working) in a room in the new brick building, built in 1892.

I've dated this photo to March of 1898 based on a calendar visible in the image. The year is not actually legible, but it's a year in which the first was a Tuesday. It also appears (not very clearly) as if the calendar is marked with quarter moon phases, and based on this interpretation, it can only be 1898.

Williamina Fleming is standing. Immediatly in front of her are Eve Leland (back row center) and Ida Woods to the right. The rest are unidentified, although the woman closest to the camera could be A. J. Cannon.

Note: Harvard identifies this as a photo including Henrietta Leavitt. She does not appear in this photo.

Earliest source: "[Women on-board ship, ca. 1900]." Harvard University Archives / UAV 630.271 (173). Harvard Libraries, olvwork431825

A group of women, most or all computers from the Observatory, on board the C.S. Minia, a cable repair ship. On the early end for possible dates of this picture, Mabel Gill (holding Fleming's hand) was hired in 1892 (assuming she had been hired at this point). At the other end, Fleming passed away in 1911.

The Minia became famous as one of two ships primarily responsible for picking up survivors (and bodies) after the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Before that, the Minia was a well-known ship under Captain Trott, also well-known for his ability to find and repair broken transatlantic telegram cables, in the deepest seas and the worst weather. He was also known for his hospitality when in port, and this photo could simply have been an opportunity to visit the ship, although he is not one of the gentlemen in this picture.

William Squares DeCarteret took over as captain in 1899 after Trott passed away, and James Adams became his chief officer. In her 1900 journal, Williamina Fleming specifically mentions a letter from "Captain Adams" about the Minia. James Adams did eventually become captain of the Minia but it seems to be at a later date. At any rate, Miss Fleming apparently had some direct connection with an officer on the ship.

Another possible connection would be the Observatory's early interest in telegraphy; they might have had much more direct contact with the ship than your average telegraph customer. Transatlantic cables were used for clock synchronization and precise longitude determinations from the very beginning. In 1873, Joseph Lovering published On the Determination of Transatlantic Longitudes by Means of the Telegraphic Cables.

Also, Captain Trott and at least one crewman were members of the Nova Scotia Institute of Science, which sent their proceedings to the Observatory, so it's possible there were other connections between this ship and the Observatory also.

Left to right:

*I found photos of both captain De Carteret and Adams, and I think it's at least possible that these men are those men, but I may have them reversed as they look like brothers to me.

**I think it looks more like Cannon, and I want it to be her because I actually have no other images (besides very large group shots at conferences) with Fleming and Cannon together. BUT, reasonable estimates of this photo's date would put Cannon in the 35 to 40 range. If this is her she certainly looks MUCH younger than the 1902 photo I have of her.

Earliest source: "[Williamina Fleming at Harvard College Observatory plate stacks, ca. 1900]." Harvard University Archives / UAV 630.271 (388). Harvard Libraries, olvwork432040

Williamina Fleming at Harvard College Observatory plate stacks. These are the "new" plate stacks in the brick building addition, built in 1902.

Earliest source: "Observatory Group [photographic group portrait, ca. 1910]." Harvard University Archives / HUPSF Observatory (14). Harvard Libraries, olvwork360662

Harvard calls this photo "Observatory Group", ca. 1910. The Internet often calls it a photo of "Pickering's Harem". I think it's from mid-1911. The lack of Williamina Fleming certainly makes it likely to be after 1911 when she passed away, and Henrietta Leavitt, also absent from the photo, was out of town until late 1911. The photo was taken in the front of the Astrophotographic Library aka, the "Brick Building", aka "Building C."

"Pickering's Harem" may be a modern sexist invention rather than a historic one. I've found no references earlier than 1976 for this phrase. On the other hand, they were much more polite about what the wrote down back then, so it may just as well be a real nickname passed down by oral tradition.

One source that DOES use that nickname, from 1982, also lists a very detailed description of the women in this photo, which I'll just quote here directly:

"At the far left of the photograph is Margaret Harwood (AB Radcliffe 1907, MA University of California 1916), who had just completed her first year as Astronomical Fellow at the Maria Mitchell Observatory. She was later appointed director there, the first woman to be appointed director of an independent observatory. Beside her in the back row is Mollie O'Reilly, a computer from 1906 to 1918. Next to Pickering is Edith Gill, a computer since 1889. Then comes Annie Jump Cannon (BA Wellesley 1884), who at that time was about halfway through classifying stellar spectra for the Henry Draper Catalogue. Behind Miss Cannon is Evelyn Leland, a computer from 1889 to 1925. Next is Florence Cushman, a computer since 1888. Behind Miss Cushman is Marion Whyte, who worked for Miss Cannon as a recorder from 1911 to 1913. At the far right of this row is Grace Brooks, a computer from 1906 to 1920. Ahead of Miss Harwood in the front row is Arville Walker (AB Radcliffe 1906), who served as assistant from 1906 until 1922. From 1922 until 1957 she held the position of secretary to Harlow Shapley, who succeeded Pickering as Director. The next woman may be Johanna Mackie, an assistant from 1903 to 1920. She received a gold medal from the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) for discovering the first nova in the constellation of Lyra. In front of Pickering is Alta Carpenter, a computer from 1906 to 1920. Next is Mabel Gill, a computer since 1892. And finally, Ida Woods (BA Wellesley 1893), who joined the corps of women computers just after graduation. In 1920 she received the first AAVSO nova medal; by 1927, she had seven bars on it for her discoveries of novae on photographs of the Milky Way."pickeringsharem

Earliest source: "[Observatory Staff in "paper doll" pose, (in line holding hands) panoramic photograph ca. 1918]." Harvard University Archives / UAV 630.271 (391). Harvard Libraries, olvwork432043

From left to right (primary identifications come from Harvard, who says the names were listed on the back):

I believe the correct names for two of these are "Mary H. Vann" and "Dorothy Block".jaavsoharwood Also, I think this is Mabel, not Edith Gill (or the few other labelled photos I've seen so far similarly mislabel the presumed sisters).

For the longest time I didn't know where pictures like this one were taken. This is an addition to the director's residence added in about 1893 that maybe doubled the size of the residence. The building is not curved, and the brick building to the right is the end of the astrophotographic addition, lying in the same plane. The wide angle just makes it look like a 90 degree bend.

Earliest source: "Cecilia Helena Payne Gaposchkin (1900-1979)." Smithsonian Institution Archives. 26 [retrieved] August 2015.sia2009-1328

I have no information on when or where these photos were taken (but I did learn about foil traceries and cinquefoil arches). But she seems fairly young, so I'd guess close to the same time as her doctoral thesis.

So about that thesis. The way the story is conventionally told, Ms. Payne discovered that the Sun was mostly made of hydrogen and helium, but THE MAN (Henry Norris Russell) wouldn't let her announce those results. Allegedly because of him she published her hydrogen and helium results as "almost certainly not real". While she did use that quote, the evidence for the rest is lacking - no letters [edit- actually there is one, although there are context issues], no early copy of her thesis. And most importantly she doesn't mention it in her autobiography, even though she is vaguely critical of Russell for other reasons (though overall she respected him deeply as a mentor).

Here's the story as I would tell it (danger - we're venturing strongly into opinion territory). Cecilia Payne published a revolutionary thesis in 1925 called Stellar Atmospheres. What she did was both ground-breaking, and fundamental to all stellar astrophysics that followed. Spectrum analysis was very important in astronomy because it could tell you what stars are made of. But until Cecilia Payne's thesis, what it couldn't do was tell you how much of each element was in the stars. Payne applied new theoretical models in quantum mechanics to the analysis of spectrums to estimate how much of each element was in the stars.

She applied this method, and published the results. And the results show that, wow, stars are almost entirely hydrogen and helium. So why did she say "almost certainly not real" if not for THE MAN? The understanding of science in those days was that everything in the universe was made of the same stuff, which is to say, just like the earth. And up until Payne's thesis, stellar spectra confirmed this - stars were made of the same stuff as the earth. And in fact, setting aside the hydrogen and helium, the rest of Payne's results confirmed this prevailing view - the ratios of elements in the stars matched pretty well with what was on the earth.

So pretend you are a scientist, a real scientist who's work is accepted by and respected by your peers. And you discover something completely unexpected and unexplained. Do you shout a complete change in orthodoxy from the rooftops, or do you publish a very cautious note about your unexpected result? If anything, Payne was brave to include the unexpected results at all, even with the "not real" notation, as there have certainly been other scientists who've simply left out unexpected data points.

This then, is why I don't like the conventional retelling. It belittles Ms. Payne's role of a responsible, professional scientist, simply to make an inappropriate point about THE MAN. If Russell did advise her to add that note, it was good advice, but I prefer to think that she was smart enough and professional enough to have published her results this way anyway.

Also, it encourages us to think of all past men as neanderthals, rather than living, breathing individuals. While sexism in general was certainly much worse then, the astronomical community was an exception, generally accepting of women as respected contributers (no doubt in part because of the legacy of Pickering's women computers). And within that community she'd found an even rarer exception at Harvard Observatory, with a small group of men and women who were actually encouraging women to advance as equals.

[But read part II in the next picture]

Earliest source: "Cecilia Helena Payne Gaposchkin (1900-1979)." Smithsonian Institution Archives. 26 [retrieved] August 2015.sia2009-1327

[continuing opinions from previous picture]

Of course, having said all that great stuff in defense of men of that era, it was only a small bubble she was in. All the friction outside that bubble held her and all women back. Let's look at THE MAN from that story. Her Mentor, Henry Norris Russell, was not at Harvard, but rather at Princeton. Russell credits his math skills to his mother and grandmother, and he also helped Annie Jump Cannon get one of her honorary degrees, so really not THE MAN he's supposed to be in the popular narrative. But Russell sent his own promising grad student to study at Harvard, Donald Menzel. He did this for the same reason everybody did research at Harvard - their amazing collection of astrophotography and spectra. But in some sense, this also put Menzel in competition with Payne as they were doing very similar research. To avoid trouble Payne's advisor (and director of the Observatory), Harlow Shapley, split up the data (I don't remember exactly how). This was for Payne and that was for Menzel.

In a telling turn, and one that resonates with lessons today about men and women competing in the modern world, Payne kept her crayons inside of her lines, but Menzel did not. He studied all the available data. Who made the right choice? I'm not sure, and I think in this particular case it didn't matter terribly much (she published an amazing thesis). However in the long run, Menzel also ended up back at Harvard, and was a director of the Observatory, a position that Payne was never able to attain. But in my opinion this almost certainly had more to do with sexism at Harvard than it did with research choices they made as grad students.

Ultimately as great as Shapley and Russell and others were for her career, there was little they could do to overcome the deeply rooted sexism in the wider world. Nor should I overstate the acceptance within the astronomical community itself. It may have been ahead of the rest of the world, but people are always products of their times. Sexism was inescapable.

Earliest source: "Observatory Women [photographic group portrait, 1925]." Harvard University Archives / HUPSF Observatory (19). Harvard Libraries, olvwork360663

Harvard says the caption is "As We Were" in the upper left corner, but they must not have scanned that or it is on the back. This is an amazing photo crossing generations of women at Harvard. It's the end of the era of women computers, and the beginning of the era of women scientists.

I found a source identifying the names. Ceclia Payne's expanded autobiography.paynerecollections My guesses were all correct (I skipped five of them).

Back row:

Middle row:

Bottom row:

Earliest source: Margaret W. Rossiter. ""Women's Work" in Science, 1880-1910." Isis vol. 71 no. 3. University of Chicago Press, September 1980.womensworksci

Unknown location. (Actually I now believe this may be the west wing of the original building, in the transit room, but after the transit instruments were removed). Source says this photo was taken 19 May, 1925.pickeringsharem

I've only just now noticed that these women are all wearing the exact same outfits as in the other 1925 photo above "As We Were", and so both photos were probably taken on the same day. They appear to be the same set of women, and based on that I've put in the five names I hadn't figured out.

My guesses on identity, left to right:

H. Wilson, A. Maury, A. Hoovens, I. Woods, A. J. Cannon, M. Howe, M. Harwood (on floor), E. Leland, A. Walker, L. Hodgdon, C. Payne (seated), E. F. Gill (standing), M. Walton Mayall, M. Gill, F. Cushman

The Cast and Crew of the Observatory Pinafore

A set of six photos of the Observatory Pinfore has recently turned up. They've been scanned by their owner, Charles Reynes, who's the great grandson of Edward Skinner King (who was almost certainly at the performance - he's in the group photo for the AAS conference where the play was staged). They are by far the best quality images I've found anywhere of the performance, and three of them haven't been found anywhere else.

I'm having a particular problem with two identifications from these photographs: G. W. Wheelwright as Winslow Upton and W. R. Ransom as Pickering. I'm hoping to identify the characters from the context of the photos, but at this point I'm not sure that will work. From the opposite end, I've attempted to find photographs of both Wheelwright and Ransom in other contexts. Neither seems to look at all like the character in the photos with the more recessed chin.

Identifications:

Bart J. Bok, unknown women, unknown man, [Wheelwright or Ransom], unknown woman, Harlow Shapley, [Ransom or Wheelwright], Arville Walker, Peter M. Millman, Arthur R. Sayer, Leon Campbell

unknown boy, Mildred Shapley, Adelaide Ames, Cecilia Payne (Gaposchkin), Henrietta Swope, Sylvia Mussels (Lindsay), Helen Sawyer (Hogg), unknown boy

Use/Copyright: Copyright held by Charles Reynes, used here with permission

The cast of the Observatory Pinafore

Identifications:

Adelaide Ames (as Rhoda G. Saunders), Bart J. Bok (as Leonard Waldo), Mildred Shapley (as computer), Unknown, Cecilia Payne (as Josephina McCormack), Peter M. Millman (as William Augustus Rogers), Henrietta Swope (as computer), Unknown, Helen Sawyer (as computer), Arthur R. Sayer (as F. E. Seagrave), Sylvia Mussels (as computer), Leon Campbell (as Arthur Searle).

Use/Copyright: Copyright held by Charles Reynes, used here with permission

A scene from the Observatory Pinafore performance, perhaps dancing.

Identifications

Bart J. Bok, Adelaide Ames, Unknown, Leon Campbell, Cecilia Payne, Peter Millman

Use/Copyright: Copyright held by Charles Reynes, used here with permission

A scene in Observatory Pinafore, where Josephina stops Professor Rogers from killing himself in despair over the defection of his helpful assistant, and circle reader, and whatever else.

This image is the most widely available image of the performance.

Identifications:

Peter Millman, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, Henrietta Swope, Mildred Shapley (daughter of Harlow and Martha Shapeley), Helen Sawyer-Hogg, Sylvia Mussells-Lindsay, Adelaide Ames, Leon Campbell.

These identifications come from the copy of this picture in the Emilo Segre Visual Archive. I've based some of my own identifcations on this list. This is my only source for Mildred Shapley and Sylvia Mussels, all the other faces I've found in other photos (to varying degrees of a satisfactory match, but at least enough of a match to improve my confidence that they're correct).

Use/Copyright: Copyright held by Charles Reynes, used here with permission

A scene from the Observatory Pinafore where Josephina is being pulled away from Professor Rogers by Seagrave and the men of Providence.

I believe this is the point in the play where Josephina is led to the "dungeon".

Identifications:

Unknown, Bart J. Bok, Unknown, Arthur Sayer, Cecilia Payne, Henrietta Swope, Mildred Shapley, Helen Sawyer, Sylvia Mussels, Adelaide Ames.

Use/Copyright: Copyright held by Charles Reynes, used here with permission

A scene from Observatory Pinfore, with Astronomers and Computers hard at work. Based on the people (and the books), this may be somewhere in the first scene of the play. If so, this could be the Winslow Upton character standing, as the right set of people are on stage for Upton's reciting of "I know the value of a kindly chorus..."

The portrait of Galileo hanging on the right still hangs in the Observatory today; it is the copy by Carlton gifted in 1890.

Identifications

Use/Copyright: Copyright held by Charles Reynes, used here with permission

A group of women computers [photographic group portrait, ca. 1900]

ca. 1900

Alternate Title: [Fleming, Williamina P., [photographic portrait, ca. 1900]." Harvard University Archives / HUP Fleming, Williamina (1). Harvard Libraries, olvwork289681

[Williamina P. Fleming, photographic portrait, ca. 1890]

Alternate Title: [Fleming, Williamina P., [photographic portrait, ca. 1900]

ca. 1890

Historical: Williamina Fleming worked at the Harvard College Observatory. She analyized stellar photographs and computed data.

Fine's Home

Fine's Home